Our History

Prepared by the Liberal Democrat History Group

The Liberal Democrats were founded in 1988, but we can trace our history back over three hundred years. This page provides a concise history of the Liberal Democrats and our Whig, Liberal and SDP predecessors. For a longer version, visit the Liberal Democrat History Group website at www.liberalhistory.org.uk.

Origins

The liberal tradition in British politics emerged during the 17th century, in the great constitutional struggles of the Civil Wars (1642–49) and the Glorious Revolution (1688). These were conflicts between those who support the existing order, with a powerful Crown and established church, and those who advocated the supremacy of parliament over the monarchy and wider toleration of different religious beliefs. In due course the conservative defence of the status quo gave rise to the Tory party; the more liberal Whigs supported reform and civil liberties.

Between 1688 and 1830, there were several long periods of one-party dominance, firstly by Whigs and later by Tories. By the early 19th century, government appeared to be representing the interests only of conservative landowners, repressing radical protest by people with neither economic security nor the right to vote. This encouraged liberals to embrace religious toleration, economic and electoral reform. In 1832, Lord Grey’s Whig government pushed through the Great Reform Act, a first, tentative, extension of the right to vote. This pushed politicians to engage more with ordinary electors and radical elements outside parliament, in the process developing the political parties we recognise today.

The Conservative Party, founded in 1835, came first, combining traditional, landed Tories in uneasy alliance with a small but influential band of free-trade Conservatives led by Sir Robert Peel. Free trade also appealed to the working classes (because it kept food cheap) and the industrial manufacturers (because it made exports easier). However, it was unwelcome to Tory farmers who benefited from agricultural protection and who opposed abolition of the Corn Laws (import duties on grain). In 1846, this issue caused the Peelites to break away. Eventually, they joined with the aristocratic Whigs and middle-class liberals and radicals elected after 1832 to create, in 1859, the Liberal Party.

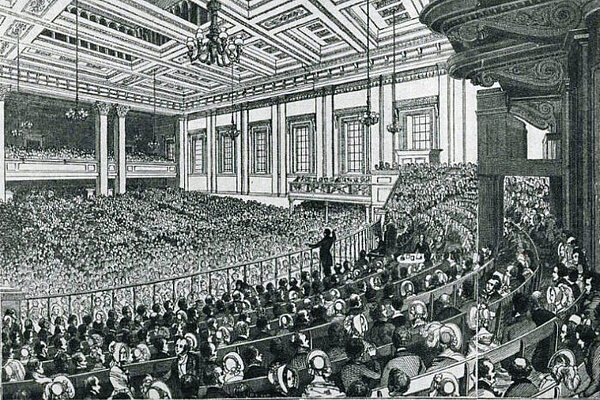

The Liberal ascendancy (1859-1911)

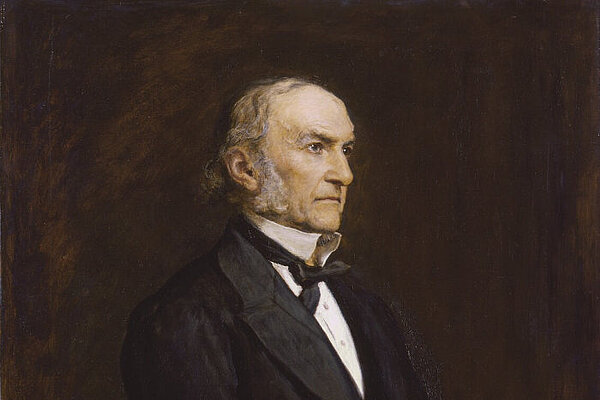

The Liberals governed Britain for most of the following thirty years, benefiting from further extensions of the franchise in 1867 and 1885. Their leader and four-times Prime Minister, William Ewart Gladstone, dominated British politics. He swept away tariffs in the interests of free trade, replaced taxes on goods and customs duties with income tax, and established parliamentary accountability for government spending.

Nonconformists strongly supported his approach to religious questions, which deeply affected basic liberties and education. After winning the 1868 election, Gladstone’s government disestablished the Church of Ireland, imposed compulsory primary education and introduced the secret ballot. In opposition after 1874, he defended the rights of oppressed minorities in the Balkans.

Gladstone’s new government from 1880 became increasingly concerned with bringing peace to Ireland, which faced sectarian divisions and economic problems. He attempted, unsuccessfully, to pass an Irish home rule bill but, in the process, split the Liberal Party, leaving the party out of power for the next twenty years, apart from a minority administration in 1892–95.

After Gladstone’s retirement in 1894, disagreements emerged between traditional liberals, who thought government should largely keep out of economic and social affairs, and the ‘New Liberals’, who argued for intervention to help the poorer sections of society – without assistance with welfare, health and education, the New Liberals argued, many people could not be truly free. Henry Campbell-Bannerman helped to heal these rifts and, with the Conservatives split over free trade and education, he led the party to a spectacular electoral landslide in 1906. An electoral pact with the new Labour Party helped to maximise the efficiency of the progressive vote.

The Liberal government of 1906–15 was one of the great reforming administrations of the century. Led by towering figures including Asquith (PM from 1908), Lloyd George and Churchill, it laid the foundations of the modern welfare state, created labour exchanges, old-age pensions and the national insurance system. This was the New Liberalism in action, removing the shackles of poverty, unemployment and ill health.

From the outset the Liberals had difficulty passing legislation through the Tory-dominated House of Lords. After the Lords rejected Lloyd George’s 1909 ‘People’s Budget’, which introduced a supertax on high earners to raise revenue for social expenditure and naval rearmament, two elections were fought in 1910 on the issue of ‘the peers versus the people’. In 1911, with the King primed to create hundreds of new Liberal peers if necessary, the Lords capitulated and the primacy of the House of Commons was definitively established.

Decline (1916-1957)

The strains of fighting the First World War brought the Liberal ascendancy to an end. The party split disastrously in 1916 over the direction of the war, when Lloyd George supplanted Asquith as Prime Minister.

In the 1918 and 1922 elections, the Lloyd George and Asquith factions fought each other. The party’s grassroots organisation fell apart, allowing the Labour Party to capture the votes of the new working-class and women voters enfranchised in 1918. Many who might later be called social democrats left the Liberals for the more evidently successful progressive alternative, the Labour Party.

The Liberals reunited around the old cause of free trade to fight the 1923 election, which left them holding the balance of power in the Commons. However, Asquith’s decision to support a minority Labour government placed the party in an awkward position and effectively polarised the political choice between Conservatives and Labour. The disastrous 1924 election relegated the party to a distant third place as the electorate increasingly opted for a straight choice between the other two parties.

Lloyd George reinvigorated the party on a radical platform of Keynesian economics for the 1929 general election, but the election results were disappointing. The Liberals split again in the 1930s, in the wake of the upheaval brought by the Great Depression, and continued to decline, despite participating in Churchill’s wartime coalition.

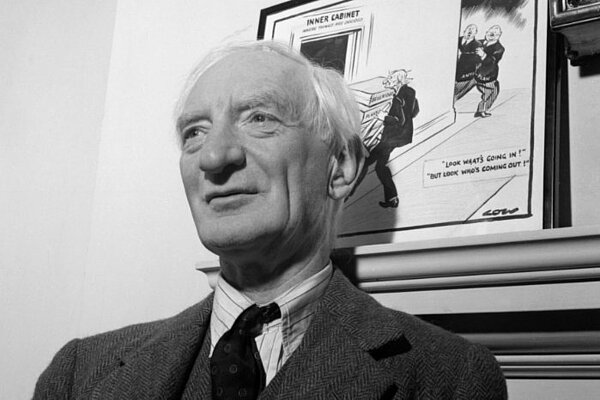

Liberalism as a philosophy was by no means dead, however; the great Liberal thinkers Keynes and Beveridge provided the doctrines underpinning government social and economic policy for the post-war period, Nevertheless, by 1957 there were only five Liberal MPs left, and just 110 constituencies had been fought at the previous general election.

Revival (1956-1987)

Jo Grimond’s election as party leader in 1956 began the revival. His vision and youthful appeal were well suited to the burgeoning television coverage of politics, and he was able to capitalise on growing dissatisfaction with the Conservatives, in power since 1951, and internal divisions in the Labour Party. He persuaded the party to adopt innovative new policies, including support for the UK’s entry to the European Community and opposition to the UK’s nuclear deterrent. In 1958, the Liberals won their first by-election for thirty years, at Torrington, and in 1962, Eric Lubbock (later Lord Avebury) won the sensational Orpington by-election.

A second revival came in the 1970s with Jeremy Thorpe as leader, peaking in the two general elections of 1974, with 19 per cent and 18 per cent of the vote, though only 14 and 13 seats, respectively. This recovery in Liberal fortunes was partly thanks to efforts to empower local communities through a community politics approach, paying attention to local problems which were often ignored by the main parties. This strategy was formally adopted by the party in 1970 and contributed to a steady growth in local authority representation, and a number of parliamentary by-election victories.

Following Labour’s defeat in the 1979 election, the party spun to the left, causing internecine strife and alienating many MPs and members. Moderate Labour leaders had worked with the Liberals both during the referendum on European Community membership in 1975, and the Lib-Lab Pact, which had kept Labour in power in 1977–78 after by-election losses had eroded their majority. On 26 March 1981 a number of them broke away from Labour to found the Social Democratic Party (SDP). The party attracted members from both Labour and Conservatives, and also brought many people into politics for the first time. The SDP and Liberals agreed to fight elections on a common platform with joint candidates.

This Alliance’s political impact was immediate, winning a string of by-election victories and topping the opinion polls for months. The two parties won 25 per cent of the vote in the 1983 general election to Labour’s 27 per cent, the best third-party performance since 1929.

The Alliance won further by-election victories in the 1983–87 Parliament, and made significant progress in local government, but there were tensions between the two leaderships. David Owen, SDP leader from 1983, was less sympathetic towards the Liberals under David Steel than his predecessor Roy Jenkins had been. Owen was determined to maintain his party’s separate (and essentially more right-wing) identity. As differences emerged, most notably on defence, the Alliance’s vote fell to 23 per cent in the 1987 election. Steel immediately proposed the merger of the two parties and, though Owen opposed it, his party voted to open talks.

A New Party (1988-2000)

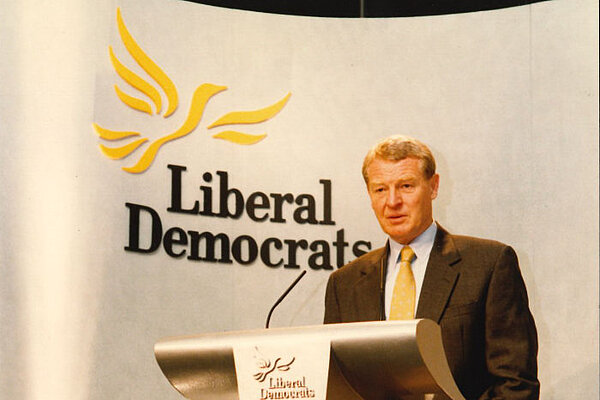

The parties spent eight months negotiating merger, with the new party’s constitution and even its name becoming subjects of sometimes bitter controversy. The Social & Liberal Democrats were born on 3 March 1988, with Paddy Ashdown elected leader in July. Owen led a significant faction of Social Democrats opposing merger, but after a couple of encouraging by-election results, his ‘continuing SDP’ declined into irrelevance, and wound itself up in 1990.

For the new party, membership, morale and finances all fell during this in-fighting. Its nadir came in the 1989 European elections, with just 6 per cent of the vote and fourth place behind the Greens. However, under Ashdown’s inspiring leadership, the Liberal Democrats slowly recovered. In 1990 they won the Eastbourne by-election, and local election advances resumed. In the 1992 general election the party won 18 per cent of the vote and 20 seats. Paddy Ashdown was consistently the most popular party leader in opinion polls, and the party’s policies, especially its pledge to raise income tax to invest extra resources in education, and its clear commitment to environmental policies, were widely praised.

Five years of weak and unpopular Conservative government after 1992 provided further opportunities in local government and the European Parliament, even after Tony Blair’s election as Labour leader, which many political commentators had predicted would destroy the Liberal Democrats. In the 1997 election, the party won 46 seats, the highest number won by a third party since 1929. Whilst its overall share of the vote fell slightly, to 17 per cent, ruthless targeting of resources on winnable constituencies showed how the detrimental effects of the first-past-the-post electoral system could be countered.

Ashdown saved the party from oblivion but ‘the project’, his attempt to work with Labour to defeat the Conservatives’ seemingly endless political hegemony, was controversial. Ashdown and Blair even discussed a formal coalition between their parties, but the scale of Labour’s triumph in 1997 made such an arrangement impossible. Nevertheless, a pre-election agreement on constitutional reform helped ensure that the Labour government introduced devolution for Scotland and Wales, reform of the House of Lords, freedom of information legislation and proportional representation for European elections.

However Blair reneged on his commitment to hold a referendum on electoral reform for Westminster, which helped convince Ashdown that the project was finished, and he stood down as leader in August 1999. Before that, he saw the party’s representation in the European Parliament rise from two to ten MEPs (the largest national contingent in the European Liberal group), and a Labour – Liberal Democrat coalition established in the new Scottish Parliament (followed by a similar coalition in the Welsh Assembly in 2000).

Changing leaders (2001-2005)

From the outset Ashdown’s successor, Charles Kennedy, was less inclined to work with Labour, focusing instead on replacing the Conservatives as the principal party of opposition. The Liberal Democrats began to benefit from the electorate’s disillusionment with New Labour, gaining ground in by-elections and local elections, and increasing their vote share in the 2001 general election to 18 per cent, with six net gains.

The terrorist attacks in the US on 11th September 2001 and the Labour government’s decision to join the US invasion of Iraq in 2003 transformed the political situation. Among the three main parties, only the Liberal Democrats opposed both the war and the steady infringements of civil liberties perpetuated by New Labour in the name of the war on terror. The party’s policy platform was popular and distinctive, with its critique of over-centralised and micro-managed public services, its proposals for a fairer tax system, its consistent support for strong environmental policies, and its opposition to Labour’s introduction of tuition fees for university students.

By-election and local election gains continued, and the Liberal Democrats emerged from the 2005 general election with 22 per cent of the vote and 62 seats, the highest number since 1923. Despite this, there was a widespread feeling amongst party members that in the wake of a deeply unpopular war, and with the Conservatives still not mounting an effective opposition, they should have done better. MPs became increasingly concerned over the party’s drift and lack of direction, Kennedy’s laid-back leadership style and his rumoured alcoholism. He was eventually persuaded to resign in January 2006, and Sir Menzies Campbell, the party’s deputy leader, was elected in his place.

The nineteen months of Campbell’s leadership was, in general, an unhappy period. Although a well-respected foreign affairs spokesman, he found it difficult to adjust to the rough and tumble of Prime Minister’s questions. While he restored a sense of purpose and professionalism to the party organisation and drove through important reforms of party policy, local election results were poor. The party’s slide in the opinion polls throughout 2007 caused panic amongst some parliamentarians and led to a systematic undermining of his leadership, culminating in his resignation in October.

Into government (2008-2015)

The election of Nick Clegg to the leadership stopped the slide in the opinion polls and stabilised party morale, and the Liberal Democrats performed strongly in local elections in 2008 and 2009. Clegg’s reaction to the world-wide credit crunch and banking crisis that followed in 2008–09, however, caused some tensions within the party, between the ‘economic liberals’ (aligned with the proposals published in 2004 in The Orange Book: Reclaiming Liberalism), who argued for a smaller state and less government intervention, and the ‘social liberals’ who pointed to the need for continued government action, in particular to reduce inequality and deal with the growing climate challenge (presented in 2007 in Reinventing the State: Social Liberalism for the 21st Century). In general the leadership won support for its proposals to cut the public deficit and prioritise public expenditure more sharply.

The Liberal Democrats entered the 2010 election with a programme including redistributive taxation, a ‘pupil premium’ to improve school education for children from poorer families, an economic stimulus package focused on low-carbon investment and a far-reaching programme of political and constitutional reform. After a dramatic campaign, featuring the country’s first-ever television debates between the three main party leaders – in which Clegg performed strongly – the Liberal Democrats ended up slightly, at 23 per cent, although the vagaries of the electoral system delivered a net loss of six seats.

The election outcome of a hung parliament gave the Liberal Democrats their first real chance of power, and negotiations for a coalition began with both Conservative and Labour parties. In the end, a coalition programme containing a substantial portion of the Liberal Democrat manifesto was agreed with the Conservatives, and for the first time in 65 years, Liberal ministers sat on the government benches; Clegg became Deputy Prime Minister.

Coalitions were relatively unfamiliar in Britain and, against a background of economic crisis and a record budget deficit, many speculated that it would be short-lived.

Yet the coalition provided stable government for a full five-year term, managed a partial recovery in government finances and oversaw a faster rate of economic growth than any other G7 country at that time. Key Liberal Democrat policies were implemented: a significant rise in the income tax threshold took an estimated three million low-paid people out of tax altogether; the ‘pupil premium’ provided more resources for schools to teach children from deprived backgrounds; and significant investment was made in renewable energy.

Liberal Democrat influence led to increases in the state pension, a higher priority to mental health, legislation for same-sex marriage, the development of an industrial strategy, the creation of the world’s first Green Investment Bank, and an expansion in the apprenticeship programme. In addition, Liberal Democrat ministers blocked or ameliorated Conservative proposals that would otherwise have adversely affected workers’ rights, disability benefits, support for young people and immigration, together with a referendum on EU membership, and extensions to covert surveillance, policies which were promptly reinstated by the Conservative government elected in 2015.

The party’s constitutional reform agenda saw major failures, however, with a change in the voting system being defeated in a referendum, reform of the House of Lords by a Conservative rebellion, and party funding reform by Conservative ministers’ desire to protect their own donors. Offsetting these disappointments were the introduction of fixed-term parliaments and the devolution of greater powers to Scotland.

The challenging economic climate, and the Conservative Party’s austerity programme, meant that difficult compromises had to be made. Liberal Democrat ministers fought, often successfully, to slow down or reverse cuts in public services and to soften their impact, but their efforts were not generally visible to the electorate. Particularly damaging was the raising of university tuition fees, which led to a disastrous loss of trust in the party and its leadership, given the party’s consistent campaign against such fees; in 2010 all Liberal Democrat candidates had pledged to vote against any rise.

Support for the party fell sharply. Between 2011 and 2015 every round of local elections saw hundreds of Liberal Democrat councillors lose their seats, and Liberal Democrat members were toppled in elections to the Scottish Parliament, the European Parliament, and finally in the 2015 general election, when only 8 of the party’s 57 MPs were re-elected, on just 7.9 per cent of the vote.

Survival and Recovery (2015-Present)

The morning after the 2015 general election, Nick Clegg resigned as leader of the party, being replaced by Tim Farron. Despite the brutal election result, there were reasons to hope: the party saw an immediate surge in membership, as many people perceived that liberal values were under threat and that the party had been punished unfairly for participation in coalition.

The Liberal Democrats campaigned strongly for a ‘remain’ vote in the referendum on Britain’s membership of the EU in June 2016, in line with their historic beliefs. The narrow vote to leave, Farron’s unequivocal statement, two days later, that the Liberal Democrats would fight the next election on the basis that the UK would be better off inside the EU, and his later call for a referendum on the final deal, gave hope to defeated remain voters and led to another surge in party membership. Wider electoral support was slow to appear, however, and Farron stepped aside after the Liberal Democrat vote fell further to 7.4 per cent in the 2017 election, despite a net gain of four MPs. He was replaced by Vince Cable, a respected former cabinet minister.

Two years of parliamentary stalemate over the terms of the Brexit deal led to a growing polarisation in the electorate, and the Liberal Democrats, fighting on a platform of ‘stop Brexit’, surged to an unexpected second place in the Euro elections in May 2019, ahead of both Labour and the Conservatives. The party also attracted several defecting MPs from both other main parties.

This spectacular success led to a degree of hubris, however, and the party overplayed its hand in the months that followed. Neither the party’s message – mainly to reverse Brexit – nor its new leader, Jo Swinson, proved popular in the general election of December 2019. Although the party’s vote share rose to 11.6 per cent, the collapse in the Labour vote left the Conservatives with a sizeable overall majority. The Liberal Democrats gained three seats but lost four of those won in 2017, including, by just 149 votes, its leader’s.

In 2020 Ed Davey thus became the party’s fifth leader in six years. He faced familiar problems in gaining media attention and recognition as head of the small fourth party at Westminster but the party’s organisation and campaigning capacity was comprehensively overhauled, efforts which paid off in local and parliamentary by-election successes as a succession of disastrous Conservative Prime Ministers comprehensively undermined support for their government.

While Labour under Keir Starmer was the main beneficiary, a series of fortuitous by-elections, often caused by allegations of misconduct by Conservative MPs, gave the Liberal Democrats four new MPs and helped to raise the profile both of the party and its leader.

When Conservative Prime Minister Rishi Sunak unexpectedly called a general election in May 2024, the Liberal Democrats were well-prepared. A variety of eye-catching stunts involving Davey were arranged to illustrate the central themes of the party programme; falling off a paddle-board on Lake Windermere, for example, reflected public outrage at repeated sewage releases into rivers and lakes.

The moving use of Davey’s personal family story in an election broadcast helped to draw attention to Liberal Democrat demands to improve social care.

The outcome of the election on 4 July 2024 was extraordinary. Although the party’s share of the vote rose by less than 1 per cent, to 12.2 per cent, the unprecedented collapse in the Conservative vote and a high degree of tactical voting by anti-Tory voters, coupled with a highly effective targeting of campaigning resources meant that, for the first time ever, the first-past-the-post electoral system did not seriously disadvantage the party. The Liberal Democrats won 72 seats, the largest number for a century. Traditional areas of strength in south-west and northern England and northern Scotland lost in 2015 were regained and joined by new seats in East Anglia and, especially, in southern England.

With substantial increases also in the Reform and Green votes, and a Labour landslide delivered on only 33.7 per cent of the vote, British politics appears to be increasingly unsettled. In a strong position as the largest third party in the House of Commons for a century, however, the Liberal Democrats are well placed to promote their vision and make a real difference to the country’s future.